Technology and tectonics

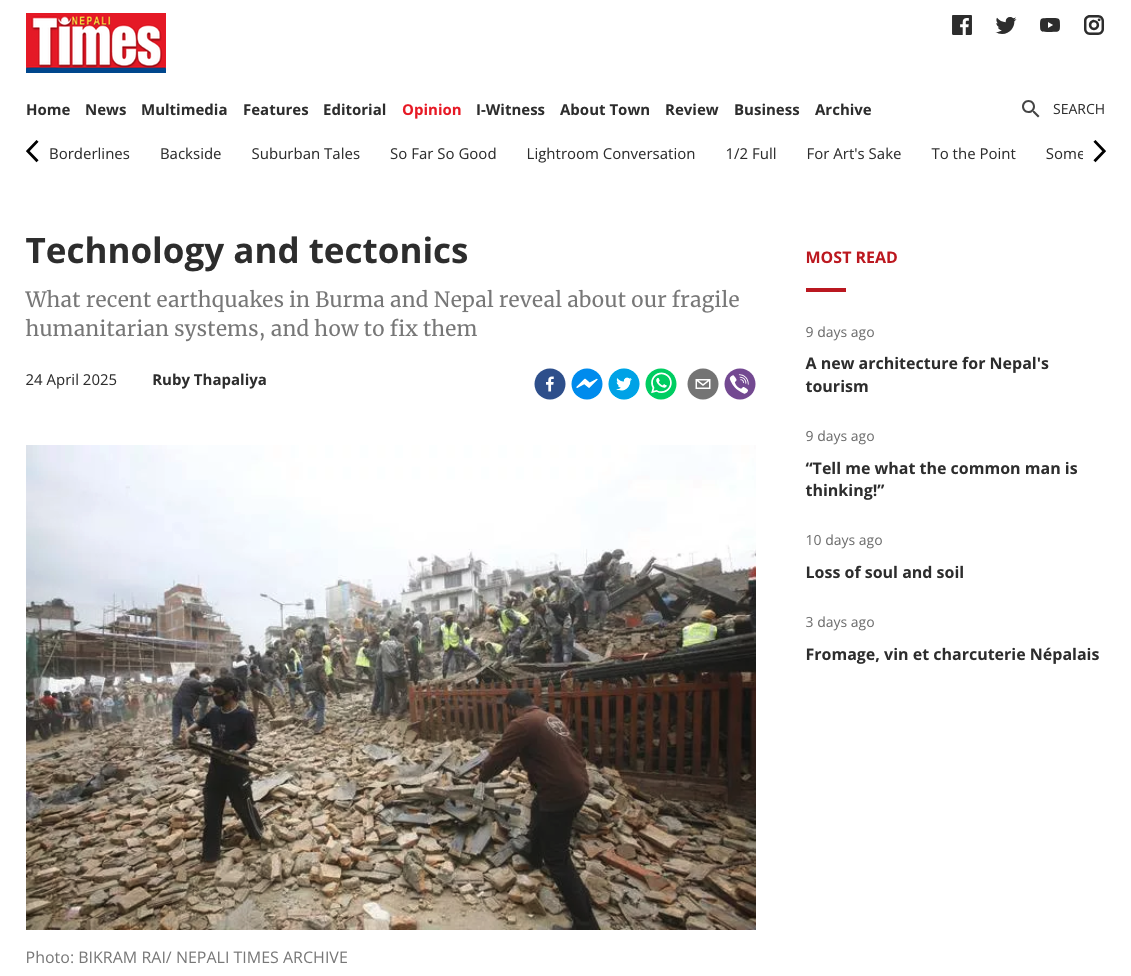

What recent earthquakes in Burma and Nepal reveal about our fragile humanitarian systems, and how to fix them.

This article by Togglecorp's Data Analyst Ruby Thapaliya appeared in the April 25, 2025 issue of Nepali Times.

“Now with every gust of wind, the smell of dead bodies fills the air.” Thar Nge, a resident of Sagaing in Burma, was speaking to the conditions in earthquake-affected areas following the country’s catastrophic 7.7M earthquake on 28 March last month.

Over four thousand people died in the disaster. For many in Nepal, scenes of the earthquake on the news and photos on social media brought back painful memories of the 2015 Nepal earthquake 10 years ago this week.

As a data analyst at Togglecorp, a private data analysis and software development company in Kathmandu, I have worked on several projects that included reviews of secondary data related to the most recent earthquakes in Burma, Morocco, Türkiye-Syria, and Nepal. The data shows a clear pattern and painful gaps in how countries respond to large-scale disasters.

Analysis conducted through the Data Entry and Exploration Platform (DEEP) reveals a clear but grim reality: the cost of earthquakes is not just measured in lives lost or buildings destroyed, but also in the speed, equity, and coordination of response efforts. Some communities rebuild, many are left behind.

The data exposed not only shared struggles between Nepal, Burma and other countries that have suffered from earthquakes, such as health system overloads and water-related disease outbreaks, but also how drastically governance and politics affect outcomes.

One theme that emerged, especially in Nepal and other countries in the region, is that earthquakes do not discriminate, but responses do. In the Burma earthquake, in some regions, 90% of homes were wiped out and over 28 hospitals were destroyed. Even as this happened, aid workers continued to face security threats while delivering aid and much-needed relief efforts.

Nepal faced similar hospital infrastructure challenges during the 2015 earthquake, where up to 90% of health facilities in districts like Sindhupalchok, Dolakha, and Gorkha were either destroyed or overwhelmed. In some areas, doctors treated patients in open fields, under tarpaulins, due to the collapse of ward buildings and lack of emergency tents.

In the aftermath of the 2023 Türkiye-Syria earthquake, cholera outbreaks surged due to failed water, sanitation and hygiene systems, and temporary tents could not keep up with displacement needs. While Nepal did not experience cholera outbreaks on that scale, post-quake diarrheal diseases and sanitation concerns were widely reported, particularly in temporary camps with inadequate toilet facilities and poor hygiene practices.

After the September 2023 earthquake in Morocco, because of the inaccessibility of many of its mountain villages, families had to dig with their bare hands to clear rubble while medical staff were forced to treat the sick and injured outdoors. Nepal shares similar geographic challenges seen in Morocco and Burma.

During the 2015 earthquake, landslides and damaged roads cut off villages in Rasuwa, Gorkha, and Lamjung, forcing rescue teams to rely on helicopters. Even today, remote hill and mountain areas, especially in Karnali and Sudurpaschim provinces, remain hard to reach during natural disasters. While earthquakes are natural, the unequal and delayed response is manmade and preventable.

Patterns across countries repeat, often due to preventable gaps. One glaring example is the chronic underfunding of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support despite growing recognition that trauma constitutes a silent second wave of devastation.

In Syria, only 3,000 people received psychological first aid, while over 1.5 million were displaced. In Burma, with over 9 million severely affected, most women and girls in areas like Sagaing and Mandalay had no access to mental health services. Healthcare systems also collapsed quickly. Hospitals like Morocco’s Mohammed VI University Hospital treated patients outdoors, and Burma saw around 25 hospitals in Mandalay, 28 in Shan, 22 in Bago and 24 in Naypyitaw damaged or destroyed.

While mobile medical units have proven effective, reaching 7,870 people in Syria, they remain underused due to poor planning and lack of pre-positioned support. Protection risks spiked in both Burma and Syria, where displaced women lacked safe shelters, lighting, or dignity kits.

Nepal’s own experience in 2015 tragically echoes these patterns: mental health issues were sidelined, hospitals in districts like Sindhupalchok and Dolakha were affected, and gender-based protection in temporary shelters was grossly inadequate. The lesson from this cross-country analysis is clear: unless countries like Nepal invest in mental health services, mobile health infrastructure, and gender-sensitive protection before disaster strikes, history will continue to repeat itself in harsh ways.

Here is where technology proves critical. Data and digital tools can identify trends across borders, strengthen coordination, and improve early response. In Nepal, digital targeting tools have helped humanitarian responders fine-tune who needs what and where, even in remote or politically unstable settings.

For example, digital tools like Vulnerability Assessment Mapping and KOBO surveys were used after Nepal’s 2015 earthquake to identify vulnerable households in hard-to-reach areas of Sindhupalchok and Dolakha, helping responders deliver aid more accurately. These platforms ensure that responses are not only faster and more efficient but also cost-effective, avoiding duplication and ensuring that limited resources go where they are needed most.

By collecting and analysing the right kind of data, including field reports, government updates, and third-party insights, the analysis through a digital-first approach can help shape a more inclusive, evidence-based response to disasters. The shift from ad hoc reaction to data-informed action allows us to save time, money, and lives.

Ultimately, earthquakes will continue to strike, but how we respond can and must change. Tools like DEEP and the use of cross-crisis digital analysis are essential for humanitarian professionals to make smarter decisions, faster. With better preparedness plans, integrated community-level responses, and real-time insights, we can transform how governments and aid agencies protect people in moments of crisis.

Earthquakes reveal more than seismic cracks: they expose the weaknesses in our humanitarian systems. And with the right tools and mindset, we can start sealing those cracks before the next tremors hit.

Link to the article: https://nepalitimes.com/opinion/technology-and-tectonics